Musso Bowie Test Results

Aug 11, 2010 5:56:57 GMT -7

Post by lrb on Aug 11, 2010 5:56:57 GMT -7

The following was forwarded to by a friend me per a request from Joe Musso. I found it very interesting and thought you might also.

From Joe Musso

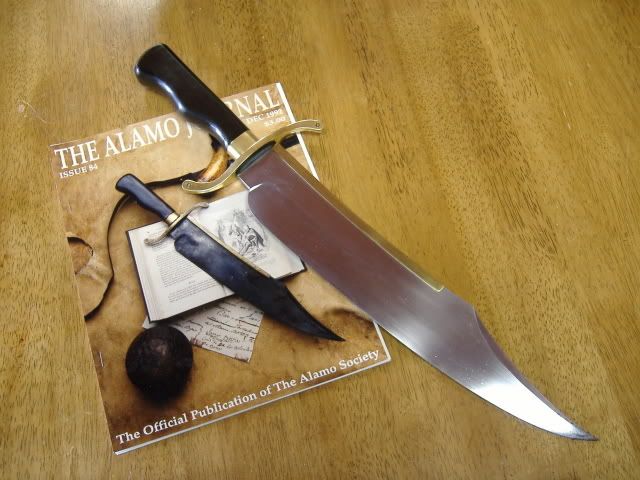

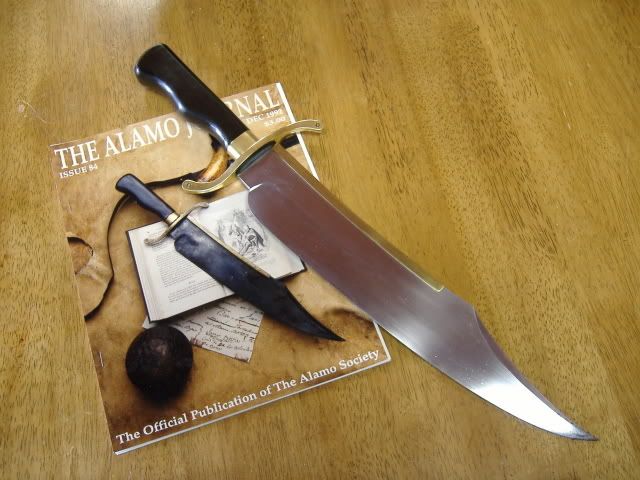

Chris Nolen contacted me about the latest postings on another forum concerning the scientific testing done on my large brass-backed bowie knife, termed by others as “The Musso Bowie.” At the same time, I would also like to thank Wick Ellerbe for his posting on this site and for sending me the latest information on the recent advancements achieved in Radiocarbon Dating. These advancements, of course, were not available when I initially had my knife tested along with the second opinions rendered between 1981 through 1992. Before discussing these advancements, however, I would like to clarify and elaborate on the statements made by Wick Ellerbe concerning my previous tests to provide a background for the original scientific claims made on my knife and correct some of the misstatements made by others. The metallurgists at the Truesdail Laboratory never referred to my knife as being made of shear steel. They described it as a “highly refined cemented product,” being hand forged “by many heating, folding and forging operations” in a charcoal furnace with alternate layers of “many thin strips of high carbon cast iron, intermediate carbon steels and low carbon, high purity wrought iron,” possibly dating back to “1600 A.D.” Dr. James L. Batson, a director of the American Bladesmith Society, subsequently described it as a form of “double shear steel” after reading all the various scientific reports and opinions offered by several different companies and individuals, including the aforementioned Truesdail Lab, the Hi-Rel Laboratory, California registered engineer Dr. Charles Miele and Smithsonian Institute metallurgist Martha Goodway. Dr. Batson concluded from these reports, both in writing to me and to others, that my knife was indeed old.

In addition, the Truesdail Labs noted that 1830s America was still using charcoal furnaces in its iron and steel production, as in this knife, while the foundries in England had switched to coal and coke during the 1700s. Truesdail also noted that by the 1860s, “modern steels (by the Bessemer Steel Process) and machine forging methods started to supersede the hand methods of producing steel articles in America.”

Contrary to Wick’s belief, however, I never refused to provide a wood sample sliver for carbon dating. It was my understanding from the metallurgists involved at the time, that carbon dating would only be helpful if the item was over 500 years old, since there was a 200 year discrepancy, one way or the other. But I did refuse to destroy the handle by sawing it in half, to send, not a wood sliver as Wick believes, but a much larger slice through the entire handle to the Forest Products Laboratory at the U.S. Forest Service in Madison, Wisconsin, for them to identify the exact species of wood through its cross-section. Since my knife’s handle still has heavy traces of ebonizing (a mixture of lamp black, shellac and linseed oil), obliterating visual examination of most of the wood grain, the authorities are at odds regarding the hardwood species used. Truesdail said that it “is typical of oak.” Dr. Batson feels that it may be red oak. Others believe it may be maple. However, since Wick says all that is needed now is a sliver from inside the handle for carbon dating, I decided to contact the Forest Products Laboratory again. They told me that they still prefer to have a 1” x 3” chunk to identify the exact wood species, but feel that they can now work with a sliver for a possible ID. They also referred me to the Laboratories of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona in Tucson for Radiocarbon Dating and their technician in charge, Todd Lange. Mr. Lange told me that it is still preferable to have the item tested to be over 500 years old because of the discrepancies I discussed above, but that they have since made great advances dating more recent items with only wood slivers. However, Mr. Lange said that accurately dating items to the the 19th century is still a problem because the Industrial Revolution, which began around the 1780s and started reaching its height in the 1830s-1840s, used fossil fuels made from organic material. This, in turn, decayed the Carbon 14 in the atmosphere during the 19th century which can now skew the Radiocarbon Dating tests, since these tests rely on the difference between the Carbon 14 and Carbon 13 in the items. Also, even if they can get an accurate reading on the wood, it would only show when the tree was cut, not when it was made into a handle. However, Mr. Lange was impressed when I told him that my knife’s steel was forged in a charcoal furnace. I concluded that I should at least attempt to have Radiocarbon Dating done both on the wood and the knife’s rust patina on the steel. Providing the wood handle wasn’t replaced at a later time or made from an earlier chunk and there is still enough Carbon 14 left in the wood and steel’s rust, these tests could be quite definitive, one way or the other, if they can get an accurate and consistent match.

I’m in discussions with them now about how best to extract the test samples. Once logged in, the turnaround time would be about two months for the Radiocarbon Dating process at the University of Arizona, as well as the wood ID at the Forest Products laboratory.

I will naturally keep everyone posted. However, regarding the previous tests done on my knife, particularly its brass that Wick discussed on this site, in the interest at getting at the truth, I had a different lab, the Hi-Rel Laboratories in Monrovia, CA do the initial brass tests on it. I told them nothing about the knife or Truesdail’s previous findings. Hi-Rel concluded that the brass “composition would be considered ‘dirty’ by modern standards, and would not be commercially available as such after about 1920.” I then eventually went back to Truesdail to do more research on Hi-Rel’s findings. Wick correctly notes the aluminum bauxite traces in my knife’s brass, but then says that a historian geologist swore that there were no bauxite deposits near the Old Washington, Arkansas forge. This is not true. A quarter of a mile north and east from Washington, is a greensand deposit that corresponds to the bauxite traces, as well as the traces of iron, silicon and phosphorous in my brass. This greensand was used in making clay crucibles for melting metals, such as copper and zinc to make brass, and molds to cast metals, such as the brass parts of my knife. The trace elements from the greensand casting mold and/or crucible would have dissolved into the molten brass. The U.S. government acquired this deposit at the outbreak of World War II for the manufacture of black powder used to ignite the smokeless charges in artillery shells. In 1992, the resident Old Washington blacksmith, Bill Hicks, sent me a quantity of greensand to have the Truesdail Labs do a Semi-Quantitative Emission Spectrographic Chemical Analysis and an X-Ray Diffraction Analysis on it. Truesdail’s findings, enumerated above, was issued in their report on August 12, 1992. This was done after Martha Goodway suggested that we do some additional tests to verify the source of the bauxite and phosphorous in the brass. Furthermore, 96 % of all the bauxite produced in the USA comes from that area of Arkansas, which also means that there is a 96% chance that this is where the knife was made—or at least the brass in it. This historic fact is something that a historian geologist should have known prior to getting into an argument with Wick and is obviously why Wick never heard from him again. For more on this greensand see:

www.basic-info-4-organic-fertilizers.com/greensand.html

Removing material, such as the surface oxides/rust, from the blade of my knife to have new Radiocarbon Tests done on it, is no problem. I would like to inform all concerned that I already had a Light Emission Spectrographic Chemical Analysis and an X-Ray Diffraction Analysis done on the surface oxides/rust. This was accomplished on the steel tang under the handle. The results ruled out that the patina/rust was created by atmospheric corrosion, salt solutions or acid. Instead, Truesdail stated “that most probably the sparse corrosion nodules and pits observed on the shank and the dense pitting and heavy corrosion on the blade are natural products built up slowly due to mild to moderate corrosive conditions over long periods of time.” Prior to these tests, however, a Macroscopic Analysis was done on the surface oxides throughout the knife to determine if parts of the knife were made up at different times through the discontinuation in these oxides—if any. They concluded that “the black corrosion products on the steel blade and comparison with the same products away from the blade guard revealed a smooth and continuous film of corrosion products without discontinuities.” The only exception being the pommel area of the handle and tang which may have had a “different type end fastener” earlier in its life. With that one possible exception, Truesdail’s observations, in turn, gives lie to the statement made by Norm Flayderman in his 2004 “The Bowie Knife” book. On page 465, he concluded that even though the “metallurgical reports…supported the antiquity of the materials used to fashion the knife,” i.e., the blade, brass strip folded over the blade’s back, crossguard, handle, etc., these tests didn’t prove “when those materials were assembled into their current form.”

Following the surface oxide analysis, material was removed from the same knife tang area for an accurate Vacuum Light Emission Spectrographic Chemical Analysis to reveal the elements in the steel. There were no modern anomalies in these elements, nor did the composition match the known commercial steels. Truesdail further noted that “the very low sulfur (0.008) and phosphorous (0.002) content are typical of some irons produced during the 16th century through the first half of the 19th century, but are rare and difficult and costly to produce in contemporary irons and steels.” A Metallographic Analysis was then done on this tang area which showed that the inclusions, slag stringers and microstructure of the steel “are typical of hand forged products as used around 1830” with wrought iron and steel made by “the cementation process.”

A Rockwell Hardness Analysis was also preformed on three different areas of the blade: the tang being 21.6Rc; the center of the blade being 32.1Rc; and the heel of the blade just forward of the ricasso, about three quarters of an inch above the cutting edge was 46Rc. The cutting edge itself could be about 50Rc. Although knives are hardened today to 58-62Rc, the cutting edge on knives and swords of years past were only taken to 45-50Rc. While the bowie knives made in Sheffield, England during the 19th century for American use were hardened throughout to about a 50Rc, the different harnesses throughout my knife show that it was spot tempered/hardened like other large, hand-forged American made bowie knives of the period, as well as the earlier Japanese samurai swords and Damascus shamshirs. The cutting edge is a hardened steel to keep it sharp, while the rest of blade is an intentionally annealed softer steel so that the blade won’t snap from a heavy blow on contact.

Regarding the balance on a large bowie knife of this kind that Alan L is concerned with, this knife, due probably to all of its forging tapers, feels incredibly light, despite its 1 Ib, 12 oz weight and 13 ¾” long, 2 ½” wide blade, which is a ¼” thick at the crossguard juncture. So much so, that years ago, A.G. Russell asked if I would let some young knifemakers hold it so they could see what the balance on a real large bowie knife should feel like.

The belief by some that a large bowie knife of this style would not have been made in the 1830s is also completely untrue. One of the basic books for bowie knife collectors and historians is Robert Abels’s “Classic Bowie Knives,” published in 1967. On page 17, he pictures Knife # 2, which has a 11 ¾” long blade, 2” wide and ¼” thick. It was made in Sheffield, England, by the firm of Charles Congreve and has the mark “WR” with a crown on the blade. “WR” is Latin for “William Rex”--King William IV of England from June 28, 1830 until his death on June 20, 1837. Following this knife is Knife # 3, which has a 11 ½” long blade, 1 ¾” wide, made by the Sheffield firm of William and Samuel Butcher. On the German silver throat of the scabbard is the inscription, “Presented to Y. Shanabrook 1840.”

Both of these two knives have large blades that are swaged along the back with sharpened clipped points, identical in style to my large knife, and can positively be dated to 1830-1840. Most authorities agree that the Sheffield cutlers initially copied the American bowie knives in the 1830s.

Regarding the brass strip along the back of my knife’s blade that some members of the Antique Bowie Knife Association refuse to believe is an authenticate feature on 19th century bowie knives, for whatever poorly researched reason, I would like to direct them to the Currier & Ives print, PUBLISHED IN 1864, titled, “Your Plan and Mine.” It shows the President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, holding a brassback bowie knife with the same style blade as the Musso Bowie. THE BRASS STRIP ALONG THE BACK OF THE BLADE IS CLEARLY DEFINED. And then there is the knife that was acquired by the American officer, Elisha Kent Kane, and presented to the first president of the American Geographic Society, Henry Grinnell, for financing Kane’s two 1850 and 1853 Arctic expeditions in search of the British explorer, Sir John Franklin. A few years before, Kane served as a special envoy from U.S. President James K. Polk to General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War. En route to Scott’s headquarters in Mexico City, Kane fought in the Battle of Napoluca on January 6, 1848, capturing and later saving the life of Mexican General Antonio Gaona and Gaona’s wounded son. Gaona showed his appreciation by treating Kane like his own son. Almost twelve years earlier, portions of Gaona’s 1st Infantry Brigade received the distinction of being the first of Santa Anna’s army to storm the north wall of the Alamo in which Jim Bowie was killed. Kane’s knife was made by Henry Schively, the cutler of Jim Bowie’s brother, Rezin. Its whereabouts have since been documented for over a 150 years. It also has a similar forged bolster like Rezin’s knife, but with a 12” long blade that has a metal strip folded over the blade’s back like the Musso Bowie.

For those interested, the Schively-Kane Knife is pictured in color and described on page 37 of Frank Thompson’s 2002 book, “The Alamo,” and was on display at the Autry National Center Museum in Los Angeles in 1998, The Buckhorn Museum in San Antonio, Texas, in 2000-2001 and the Texas State History Museum in Austin, Texas, throughout 2002. In addition, I discussed the Schively-Kane knife, along with the Edwin Forrest Knife and the guardless coffin knives attributed to James Black, in my Letter to the Editor in the current October 2010 issue of Blade Magazine.

Lastly, we have, of course, the 1855 memoirs of Jim Bowie’s commanding officer and friend, as well as one of the last persons to see him alive, Sam Houston. The memoirs show Houston holding a knife, identical to the Musso Bowie, while formulating his battle plan of victory at San Jacinto. This illustration was done by Jacob Dallas, the cousin of Houston’s friend, U.S. Vice President George Mifflin Dallas, for whom Dallas, Texas, is named after.

Although Norm Flayderman says he is keeping an open mind to brassback bowie knives, for whatever reason he ignored the Schively-Kane Knife, the 1864 Currier & Ives brassback bowie knife picture and Houston’s 1855 illustration of the identical style Musso Bowie, as well as the original brassback clip-pointed folding bowie knife in the Smithsonian Institute that was the basis for the 1952 “The Iron Mistress” film knife, when he discussed the subject in his book. Furthermore, Flayderman also didn’t even bother to mention the knife with metal strip folded over the blade’s spine that he pictures on the back of his own book’s dust jacket cover.

However, I’ll leave it others to ascertain why some individuals in the Antique Bowie Knife Association and perhaps on this website prefer to base their dogmatic opinions on inadequate, inaccurate and/or selective research.

Thank you for allowing me to impart my research in this discussion,

Joe Musso

From Joe Musso

Chris Nolen contacted me about the latest postings on another forum concerning the scientific testing done on my large brass-backed bowie knife, termed by others as “The Musso Bowie.” At the same time, I would also like to thank Wick Ellerbe for his posting on this site and for sending me the latest information on the recent advancements achieved in Radiocarbon Dating. These advancements, of course, were not available when I initially had my knife tested along with the second opinions rendered between 1981 through 1992. Before discussing these advancements, however, I would like to clarify and elaborate on the statements made by Wick Ellerbe concerning my previous tests to provide a background for the original scientific claims made on my knife and correct some of the misstatements made by others. The metallurgists at the Truesdail Laboratory never referred to my knife as being made of shear steel. They described it as a “highly refined cemented product,” being hand forged “by many heating, folding and forging operations” in a charcoal furnace with alternate layers of “many thin strips of high carbon cast iron, intermediate carbon steels and low carbon, high purity wrought iron,” possibly dating back to “1600 A.D.” Dr. James L. Batson, a director of the American Bladesmith Society, subsequently described it as a form of “double shear steel” after reading all the various scientific reports and opinions offered by several different companies and individuals, including the aforementioned Truesdail Lab, the Hi-Rel Laboratory, California registered engineer Dr. Charles Miele and Smithsonian Institute metallurgist Martha Goodway. Dr. Batson concluded from these reports, both in writing to me and to others, that my knife was indeed old.

In addition, the Truesdail Labs noted that 1830s America was still using charcoal furnaces in its iron and steel production, as in this knife, while the foundries in England had switched to coal and coke during the 1700s. Truesdail also noted that by the 1860s, “modern steels (by the Bessemer Steel Process) and machine forging methods started to supersede the hand methods of producing steel articles in America.”

Contrary to Wick’s belief, however, I never refused to provide a wood sample sliver for carbon dating. It was my understanding from the metallurgists involved at the time, that carbon dating would only be helpful if the item was over 500 years old, since there was a 200 year discrepancy, one way or the other. But I did refuse to destroy the handle by sawing it in half, to send, not a wood sliver as Wick believes, but a much larger slice through the entire handle to the Forest Products Laboratory at the U.S. Forest Service in Madison, Wisconsin, for them to identify the exact species of wood through its cross-section. Since my knife’s handle still has heavy traces of ebonizing (a mixture of lamp black, shellac and linseed oil), obliterating visual examination of most of the wood grain, the authorities are at odds regarding the hardwood species used. Truesdail said that it “is typical of oak.” Dr. Batson feels that it may be red oak. Others believe it may be maple. However, since Wick says all that is needed now is a sliver from inside the handle for carbon dating, I decided to contact the Forest Products Laboratory again. They told me that they still prefer to have a 1” x 3” chunk to identify the exact wood species, but feel that they can now work with a sliver for a possible ID. They also referred me to the Laboratories of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona in Tucson for Radiocarbon Dating and their technician in charge, Todd Lange. Mr. Lange told me that it is still preferable to have the item tested to be over 500 years old because of the discrepancies I discussed above, but that they have since made great advances dating more recent items with only wood slivers. However, Mr. Lange said that accurately dating items to the the 19th century is still a problem because the Industrial Revolution, which began around the 1780s and started reaching its height in the 1830s-1840s, used fossil fuels made from organic material. This, in turn, decayed the Carbon 14 in the atmosphere during the 19th century which can now skew the Radiocarbon Dating tests, since these tests rely on the difference between the Carbon 14 and Carbon 13 in the items. Also, even if they can get an accurate reading on the wood, it would only show when the tree was cut, not when it was made into a handle. However, Mr. Lange was impressed when I told him that my knife’s steel was forged in a charcoal furnace. I concluded that I should at least attempt to have Radiocarbon Dating done both on the wood and the knife’s rust patina on the steel. Providing the wood handle wasn’t replaced at a later time or made from an earlier chunk and there is still enough Carbon 14 left in the wood and steel’s rust, these tests could be quite definitive, one way or the other, if they can get an accurate and consistent match.

I’m in discussions with them now about how best to extract the test samples. Once logged in, the turnaround time would be about two months for the Radiocarbon Dating process at the University of Arizona, as well as the wood ID at the Forest Products laboratory.

I will naturally keep everyone posted. However, regarding the previous tests done on my knife, particularly its brass that Wick discussed on this site, in the interest at getting at the truth, I had a different lab, the Hi-Rel Laboratories in Monrovia, CA do the initial brass tests on it. I told them nothing about the knife or Truesdail’s previous findings. Hi-Rel concluded that the brass “composition would be considered ‘dirty’ by modern standards, and would not be commercially available as such after about 1920.” I then eventually went back to Truesdail to do more research on Hi-Rel’s findings. Wick correctly notes the aluminum bauxite traces in my knife’s brass, but then says that a historian geologist swore that there were no bauxite deposits near the Old Washington, Arkansas forge. This is not true. A quarter of a mile north and east from Washington, is a greensand deposit that corresponds to the bauxite traces, as well as the traces of iron, silicon and phosphorous in my brass. This greensand was used in making clay crucibles for melting metals, such as copper and zinc to make brass, and molds to cast metals, such as the brass parts of my knife. The trace elements from the greensand casting mold and/or crucible would have dissolved into the molten brass. The U.S. government acquired this deposit at the outbreak of World War II for the manufacture of black powder used to ignite the smokeless charges in artillery shells. In 1992, the resident Old Washington blacksmith, Bill Hicks, sent me a quantity of greensand to have the Truesdail Labs do a Semi-Quantitative Emission Spectrographic Chemical Analysis and an X-Ray Diffraction Analysis on it. Truesdail’s findings, enumerated above, was issued in their report on August 12, 1992. This was done after Martha Goodway suggested that we do some additional tests to verify the source of the bauxite and phosphorous in the brass. Furthermore, 96 % of all the bauxite produced in the USA comes from that area of Arkansas, which also means that there is a 96% chance that this is where the knife was made—or at least the brass in it. This historic fact is something that a historian geologist should have known prior to getting into an argument with Wick and is obviously why Wick never heard from him again. For more on this greensand see:

www.basic-info-4-organic-fertilizers.com/greensand.html

Removing material, such as the surface oxides/rust, from the blade of my knife to have new Radiocarbon Tests done on it, is no problem. I would like to inform all concerned that I already had a Light Emission Spectrographic Chemical Analysis and an X-Ray Diffraction Analysis done on the surface oxides/rust. This was accomplished on the steel tang under the handle. The results ruled out that the patina/rust was created by atmospheric corrosion, salt solutions or acid. Instead, Truesdail stated “that most probably the sparse corrosion nodules and pits observed on the shank and the dense pitting and heavy corrosion on the blade are natural products built up slowly due to mild to moderate corrosive conditions over long periods of time.” Prior to these tests, however, a Macroscopic Analysis was done on the surface oxides throughout the knife to determine if parts of the knife were made up at different times through the discontinuation in these oxides—if any. They concluded that “the black corrosion products on the steel blade and comparison with the same products away from the blade guard revealed a smooth and continuous film of corrosion products without discontinuities.” The only exception being the pommel area of the handle and tang which may have had a “different type end fastener” earlier in its life. With that one possible exception, Truesdail’s observations, in turn, gives lie to the statement made by Norm Flayderman in his 2004 “The Bowie Knife” book. On page 465, he concluded that even though the “metallurgical reports…supported the antiquity of the materials used to fashion the knife,” i.e., the blade, brass strip folded over the blade’s back, crossguard, handle, etc., these tests didn’t prove “when those materials were assembled into their current form.”

Following the surface oxide analysis, material was removed from the same knife tang area for an accurate Vacuum Light Emission Spectrographic Chemical Analysis to reveal the elements in the steel. There were no modern anomalies in these elements, nor did the composition match the known commercial steels. Truesdail further noted that “the very low sulfur (0.008) and phosphorous (0.002) content are typical of some irons produced during the 16th century through the first half of the 19th century, but are rare and difficult and costly to produce in contemporary irons and steels.” A Metallographic Analysis was then done on this tang area which showed that the inclusions, slag stringers and microstructure of the steel “are typical of hand forged products as used around 1830” with wrought iron and steel made by “the cementation process.”

A Rockwell Hardness Analysis was also preformed on three different areas of the blade: the tang being 21.6Rc; the center of the blade being 32.1Rc; and the heel of the blade just forward of the ricasso, about three quarters of an inch above the cutting edge was 46Rc. The cutting edge itself could be about 50Rc. Although knives are hardened today to 58-62Rc, the cutting edge on knives and swords of years past were only taken to 45-50Rc. While the bowie knives made in Sheffield, England during the 19th century for American use were hardened throughout to about a 50Rc, the different harnesses throughout my knife show that it was spot tempered/hardened like other large, hand-forged American made bowie knives of the period, as well as the earlier Japanese samurai swords and Damascus shamshirs. The cutting edge is a hardened steel to keep it sharp, while the rest of blade is an intentionally annealed softer steel so that the blade won’t snap from a heavy blow on contact.

Regarding the balance on a large bowie knife of this kind that Alan L is concerned with, this knife, due probably to all of its forging tapers, feels incredibly light, despite its 1 Ib, 12 oz weight and 13 ¾” long, 2 ½” wide blade, which is a ¼” thick at the crossguard juncture. So much so, that years ago, A.G. Russell asked if I would let some young knifemakers hold it so they could see what the balance on a real large bowie knife should feel like.

The belief by some that a large bowie knife of this style would not have been made in the 1830s is also completely untrue. One of the basic books for bowie knife collectors and historians is Robert Abels’s “Classic Bowie Knives,” published in 1967. On page 17, he pictures Knife # 2, which has a 11 ¾” long blade, 2” wide and ¼” thick. It was made in Sheffield, England, by the firm of Charles Congreve and has the mark “WR” with a crown on the blade. “WR” is Latin for “William Rex”--King William IV of England from June 28, 1830 until his death on June 20, 1837. Following this knife is Knife # 3, which has a 11 ½” long blade, 1 ¾” wide, made by the Sheffield firm of William and Samuel Butcher. On the German silver throat of the scabbard is the inscription, “Presented to Y. Shanabrook 1840.”

Both of these two knives have large blades that are swaged along the back with sharpened clipped points, identical in style to my large knife, and can positively be dated to 1830-1840. Most authorities agree that the Sheffield cutlers initially copied the American bowie knives in the 1830s.

Regarding the brass strip along the back of my knife’s blade that some members of the Antique Bowie Knife Association refuse to believe is an authenticate feature on 19th century bowie knives, for whatever poorly researched reason, I would like to direct them to the Currier & Ives print, PUBLISHED IN 1864, titled, “Your Plan and Mine.” It shows the President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, holding a brassback bowie knife with the same style blade as the Musso Bowie. THE BRASS STRIP ALONG THE BACK OF THE BLADE IS CLEARLY DEFINED. And then there is the knife that was acquired by the American officer, Elisha Kent Kane, and presented to the first president of the American Geographic Society, Henry Grinnell, for financing Kane’s two 1850 and 1853 Arctic expeditions in search of the British explorer, Sir John Franklin. A few years before, Kane served as a special envoy from U.S. President James K. Polk to General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War. En route to Scott’s headquarters in Mexico City, Kane fought in the Battle of Napoluca on January 6, 1848, capturing and later saving the life of Mexican General Antonio Gaona and Gaona’s wounded son. Gaona showed his appreciation by treating Kane like his own son. Almost twelve years earlier, portions of Gaona’s 1st Infantry Brigade received the distinction of being the first of Santa Anna’s army to storm the north wall of the Alamo in which Jim Bowie was killed. Kane’s knife was made by Henry Schively, the cutler of Jim Bowie’s brother, Rezin. Its whereabouts have since been documented for over a 150 years. It also has a similar forged bolster like Rezin’s knife, but with a 12” long blade that has a metal strip folded over the blade’s back like the Musso Bowie.

For those interested, the Schively-Kane Knife is pictured in color and described on page 37 of Frank Thompson’s 2002 book, “The Alamo,” and was on display at the Autry National Center Museum in Los Angeles in 1998, The Buckhorn Museum in San Antonio, Texas, in 2000-2001 and the Texas State History Museum in Austin, Texas, throughout 2002. In addition, I discussed the Schively-Kane knife, along with the Edwin Forrest Knife and the guardless coffin knives attributed to James Black, in my Letter to the Editor in the current October 2010 issue of Blade Magazine.

Lastly, we have, of course, the 1855 memoirs of Jim Bowie’s commanding officer and friend, as well as one of the last persons to see him alive, Sam Houston. The memoirs show Houston holding a knife, identical to the Musso Bowie, while formulating his battle plan of victory at San Jacinto. This illustration was done by Jacob Dallas, the cousin of Houston’s friend, U.S. Vice President George Mifflin Dallas, for whom Dallas, Texas, is named after.

Although Norm Flayderman says he is keeping an open mind to brassback bowie knives, for whatever reason he ignored the Schively-Kane Knife, the 1864 Currier & Ives brassback bowie knife picture and Houston’s 1855 illustration of the identical style Musso Bowie, as well as the original brassback clip-pointed folding bowie knife in the Smithsonian Institute that was the basis for the 1952 “The Iron Mistress” film knife, when he discussed the subject in his book. Furthermore, Flayderman also didn’t even bother to mention the knife with metal strip folded over the blade’s spine that he pictures on the back of his own book’s dust jacket cover.

However, I’ll leave it others to ascertain why some individuals in the Antique Bowie Knife Association and perhaps on this website prefer to base their dogmatic opinions on inadequate, inaccurate and/or selective research.

Thank you for allowing me to impart my research in this discussion,

Joe Musso